By Stuart Mason Dambrot, Synthesist | Futurist, Critical Thought

When envisioning, planning for or attempting to create a future scenario, an often-overlooked problem is ignoring the Zeitgeist – the dominant school of thought that typifies and influences the culture of a particular period in time. As a result, such scenarios have an overly narrow focus on that specific scenario alone. As a result, institutionalized aspects of human behavior do not change in isolation, but are nonetheless conceptualized as separate entities.

As a result, the scenario in question – whether, for example, political, technological, economic, or sociocultural – will carry a higher than necessary probability of failure to materialize or, if apparently successful at first, to sustain the structural and functional design originally intended. This then leads to increasing divergence from that initial design, and so requires propaganda – and more often than not, ultimately the application of force – to maintain power.

To understand why this ultimately counterproductive approach to governance characterizes human behavior, it’s necessary to look in a direction rarely addressed in political dialogue: the evolution of H. sapiens neurobiology.

The typically unarticulated factors at the core of this issue follow. While clearly interrelated, these will first be addressed individually before being integrated into a cohesive proposition that presents possible Transhumanism efforts in science and technology that might provide solutions to this pervasive and persistent dilemma. In short, H. sapiens:

- unconsciously forms in-groups and out-groups that compete for legitimacy and power

- is a social species with (typically) an alpha male-based structural hierarchy

- mistakes beliefs and observation-based inductive inference for knowledge and fact-based deductive conclusions, respectively

- has a cognitive system based largely on emotion and metaphor

- exhibits cognitive bias and often lacks meaningful self-awareness

While this chapter is obviously not an academic treatment, we can nevertheless deconstruct our cognitive and behavioral patterns in the light of these defining characteristics in the interest of transcending our current political systems.

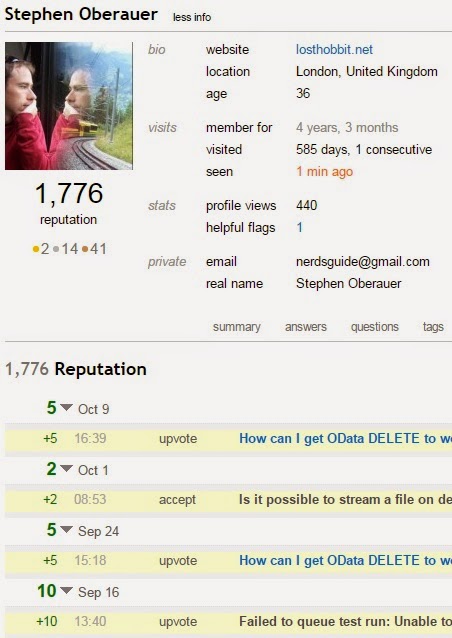

Human Phylogeny. Credit: Stearns & Hoekstra (2005). Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press [xvi]

The Nature of Human Nature

We can learn a great deal about ourselves by observing chimpanzees and bonobos – our closest living primate relatives. Our DNA differs from that of both species by only 1.2 % (although they differ from each other in both DNA and social behavior [i]). We all share a common non-human ancestor some eight to six million years ago [ii], while chimpanzees and bonobos diverged from each other some 1.5-2 million years ago. As such, it is more enlightening to say that we’re like them than the typical view that they’re like us – and what’s enlightening is the range and specificity of behaviors that we share.

In addition to chimpanzee behaviors observed in the lab that are associated with high intelligence – such as recognizing themselves in a mirror and communicating through a written language – it is their untrained behavior in the wild that is truly revealing. This includes having a dominant alpha male leader; ingesting medicinal plants for a range of ailments; using leaves for bodily hygiene; raiding and decimating other chimpanzee troops to acquire their territory and food resources; and – in perhaps the most telling example – practicing the art of deception: In a troop of male chimpanzees walking in single file though the forest in search of food, a single individual spots a piece of fallen fruit off to one side of the trail. That individual then turns to the opposite side of the trail and looks at the forest floor with an exaggerated stare. Once the other chimpanzees are straining to see what he is apparently looking at (as humans would do), he leaps to the fruit and grabs it for himself.

In other words, deception is a trait we share with chimpanzees that provides a highly functional evolutionary advantage in a hierarchical social species based on alpha-structured resource acquisition and control.

Interestingly, bonobos have a very different culture, being matriarchal and peaceful. For example, while chimpanzees engage in copulation primarily for propagation – with high-ranking males monopolizing and guarding females in estrus – bonobos engage in sex to reduce tension and resolve conflicts, offer a greeting, form social bonds, elicit social or food benefits (young females, in particular, may copulate with a male then take or receive food from him), and other reasons. Unlike chimpanzees, bonobos are female-dominant with an alpha female social hierarchy, and in the wild have not been observed to exhibit lethal aggression.

Since we exhibit qualities of both species, the question becomes one of scale. Specifically, at individual and small scales, we tend towards less aggressive bonobo-like behaviors – but within large-scale societal agglomerations artificially delineated on the basis of an abstract definition (in this discussion, politics, as well as economics, organized religion, nationalism, militarism, and so on), we engage in more chimpanzee-like aggressive behaviors.

Either way, in many ways we are (so to speak) chimps in suits.

This is the heritage we carry forward, even with our uniquely powerful brains. What’s even more astounding, however, is the revelatory finding reported in recently-published research [iii],[iv] that a single genetic mutation appears responsible for the uniquely neuron-dense neocortex we share with two other extinct hominin species, Neanderthals and Denisovans. (That said, since these two species did not create a robust culture as we have, it appears that more neurons are not enough: our cognitive abilities appear to rely on other factors, such as how those neurons are interconnected.) The point is that this unique gene is one out of the some 20,000 genes that comprise our genome [v], most of which share with chimpanzees and bonobos.

In-group Favoritism and Intergroup Aggression

That an us-versus-them mentality drives our social behavior [vi],[vii] is obvious – sometimes tragically – in politics, religion, nationalism, sports, multiplayer video games, and other large interest- and/or belief-based agglomerations. What is not fully realized is how little it takes for even a small number of strangers to quickly bond on the basis of almost anything – even eye color [viii], a random grouping, or a grouping based on an otherwise meaningless object or task.

In one such experiment [ix], investigators studied collaborations of 10-person groups in which some members were collocated and others were isolated. Individuals bought and sold shapes from each other in order to form strings of shapes, where strings represent joint projects, and each individual’s shapes represented his or her unique skills. The investigators found that the collocated members formed an in-group, excluding the isolates – but the isolates also formed an in-group.

In short, based on little or no substance we automatically form in-groups that are biased against and aggressive towards corresponding out-groups – without being aware of doing so. This characteristic alone is responsible for much of our discord, violence and dysfunctional governance.

Tools, Language and Logic

While other animals make and use tools – such as chimpanzees fashioning, along with other tools, “termite fishing toolkits” from twigs and branches [x] – we alone have created tools, structures and technologies that have dramatically transformed, and will increasingly transform, ourselves and our planet and exoplanetary environments. At the same time, our spoken and then written ability to communicate with other members of our species graduated from signs to symbols, leading to an incredibly rich language fueled by our ability to generalize and categorize the patterns we detect through our senses. The final component of this intellective triptych is the emergence of reason (using existing knowledge to draw conclusions, make predictions, or construct explanations) and its formal representation, logic.

While there are far too many reasoning methods and logic systems to cover here, the three that matter most in this discussion are deduction, induction and abduction[xi]. Deductive reasoning is a logical process which derives a definite conclusion as a logical consequence of premises that are assumed to be true. On the other hand, inductive reasoning infers probabilistic generalizations from specific observations, where the conclusion can be false even if all of the premises are true. Finally, abductive reasoning reverses the direction of inference, inferring a probable premise, cause or explanation for an observed consequence.

In this discussion, we’re primarily concerned with deduction and induction. (Abduction comes into play where, for example, we envision a future state – political or otherwise – and “reverse engineer” the conditions that would likely lead to that state – an approach well-suited to transpolitics, if only we could have universal agreement on that future state should be.)

In the case of deduction and induction, there are three critical issues that often go overlooked in daily discourse (“a watched kettle never boils”), but oftentimes – as a reminder of a chimpanzee deceiving others in his group in the pursuit of self-interest – are intentionally leveraged in rhetorical speech, political dialogue and propaganda: (1) depending on the truth of the original premises, a deductive conclusion can be true or false even if logically valid; (2) a deductive conclusion can be valid even if the premise is false; and (3) an inductive inference is erroneously thought to be or presented as a deductive conclusion.

As such, a central goal of a future transpolitical environment is educating, encouraging and supporting the abandonment of generating misleading communications by intentionally or unintentionally manipulating logic.

The Invisible Hand of Emotion: Rationality as an Afterthought

Rationality is the quality or state of being reasonable, based on facts or reason. Rationality implies the conformity of one’s beliefs with one’s reasons to believe, or of one’s actions with one’s reasons for action. However, it’s not that simple: What is considered rational is relative, in that the operational cognitive model – reflected in often unspoken framing – determines whether or not a decision is rational or not – for example, whether the model primarily values the individual or the group.

Moreover, unlike our advanced neocortical cognitive capabilities, emotions arise in a much more primitive part of our brain – the limbic system. Nevertheless, emotions influence and interact with cognition in a number of important ways. Perhaps more importantly, emotion is causative in decision-making by unobtrusively engaging prior to cognitive activity, reasoning and rational thought. A case in point: Scientists presented subjects with what is known as a visual choice reaction task, in which a button had to be pressed when an image was presented. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to image the brain areas active during this task, the researchers observed activity not in the part of the neocortex where rational decisions are made, but rather in a deeper brain area called the anterior cingulate cortex, which is associated with error detection, motor activity, conscious experience and, in this experiment, possibly, acting as an interface between limbic and cortical systems [xii].

Another factor that can be used in rhetorical or persuasive communications to facilitates a speaker’s ability to control the emotional component of cognition, memory and language is that we describe and understand the world primarily through metaphor [xiii] – a word or phrase used to compare two unlike objects, ideas, thoughts or feelings to provide a clearer description of one using the other.

Relatedly, a process known as framing – how individuals, groups, and societies organize, perceive, and communicate about reality – is used by mass media sources, political or social movements, political leaders, or other actors and organizations to make false or exaggerated comparisons that can be persuasive when a logical argument would not be.

Know Thyself

A field of inquiry since antiquity in both Eastern and Western philosophy, self-awareness (also referred to as self-knowledge, mindfulness, metacognition [xiv], and other terms) is the practice of intentional, non-judgmental introspection of our patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting. The goal is to develop the ability to go beyond mere consciousness of one’s body and environment to gain a deeper understanding of one’s assumptions, biases, predilections, biases, motives, values, emotions, thoughts, metaphors, and other typically unarticulated contributors to and causes of otherwise unexamined habits of cognition and behavior. Self-awareness is achieved through a variety of channels, including meditation, counseling, psychotherapy, education, and training.

The need for this new perspective is obvious. Our history – past, present and (at least in the short-to medium term) future – is marked by an endless series of violent practices in what is often archaically referred to as man’s inhumanity to man. Moreover, these large-scale events, such as invasion, war, genocide, atrocities, religious hatred, violent racism, abusive sexism, induced poverty, and exploitation, have their roots and counterparts in small-scale and individual antisocial – and sometimes seen as idiopathic – behaviors like lying, cheating, stealing, interpersonal abuse and violence, and other unfortunately everyday activities. When we do assign cause, we tend to point to a variety of secondary and tertiary causes of such behaviors. However, everything we do – not only the above, but all of our technology, economics, philosophy, beliefs, creativity, and most assuredly politics – is a primary expression or instantiation of a neural state of which we are seldom aware and therefore rarely articulate or consider as causative or even relevant.

In the specific domain of transpolitical change, the aforementioned issue of scale is central by virtue of the large number of persons involved in relation to the practice of self-awareness being de facto an individual pursuit. Given our near-universal priority being growth, productivity and wealth, a global environment supporting self-awareness appears to be a far-future scenario – an enlightened society that no longer requires laws defining, and enforcement maintaining, restricted and coerced behavior. In this scenario, individual self-awareness is an essential cornerstone of an enlightened transpolitical system in which the strong do not victimize the weak [xv].

The Zeitgeist of Change

Taking these powerful, universal, and often silent factors into question, and the way they influence – and when acted upon unthinkingly, determine – our thoughts, priorities, decisions, communications, and behavior, we can begin to see ourselves in aggregate as an enormously intelligent species that still prioritizes competitive self-interest, and that thinks and acts based more on instinct and impulse than reflection and insight. This clear and present reality is the fundamental causative determinant in the cyclical nature of political dialectic, as well as the generative force in creating the illusion that our social institutions – be they political, national, religious, economic, military, scientific, creative, or any other of the myriad aspects of human behavior – are rationally-created entities that have an existence of their own outside the realm of humans acting in groups of various sizes, values, goals, and resources.

In order to successfully and consistently consider societal evolution as a whole rather than just focusing on alternate political systems, and thereby to maximize the probability of creating non-dystopic futures, we would be best served by adopting what might be considered a medical model. In other words, to stop treating what can be considered the symptoms of human nature – that is, dysfunctional politics and other agglomerative In/Out group-mediated social institutions – we need to:

- use that awareness to move beyond our evolutionary impulses to acquire power and control over others

- foster a deeper awareness of our emotion- and self-interest-driven motivations

- learn through guidance and practice how to decouple those impulses from our political behavior

- use this new self-knowledge to model non-exploitative transpolitical systems that are no longer manifestations of evolutionary drives, unexamined beliefs and experience-based neocortical models of perceived value and alpha dominance

- use these models to design transpolitical constructs that implement our rational and cooperative traits

References

[i] The Social Behavior of Chimpanzees and Bonobos (http://primate.uchicago.edu/Stanford.pdf)

[ii] Comparing the human and chimpanzee genomes: Searching for needles in a haystack (http://genome.cshlp.org/content/15/12/1746.full)

[iii] Xeroxed gene may have paved the way for large human brain (http://news.sciencemag.org/biology/2015/02/xeroxed-gene-may-have-paved-way-large-human-brain?intcmp=highwire)

[iv] Human-specific gene ARHGAP11B promotes basal progenitor amplification and neocortex expansion (http://www.sciencemag.org/content/early/2015/02/25/science.aaa1975)

[v] The shrinking human protein coding complement: are there now fewer than 20,000 genes? (http://arxiv.org/abs/1312.7111)

[vi] Evolution of in-group favoritism (www.nature.com/srep/2012/120621/srep00460/full/srep00460.html)

[vii] Intergroup Bias (http://www.psych.purdue.edu/~willia55/392F-%2706/HewstoneRubinWillis.pdf)

[viii] In-groups, out-groups, and the psychology of crowds (https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/fulfillment-any-age/201012/in-groups-out-groups-and-the-psychology-crowds)

[ix] In-group/Out-group Effects in Distributed Teams: An Experimental Simulation (http://www.ics.uci.edu/~jsolson/publications/DistributedCollaboratories/Bos_IngroupOutgroup.pdf)

[x] Chimps Shown Using Not Just a Tool but a “Tool Kit” (http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/10/1006_041006_chimps.html)

[xi] Deductive Reasoning vs. Inductive Reasoning (http://www.livescience.com/21569-deduction-vs-induction.html)

[xii] Volition to Action—An Event-Related fMRI Study (http://www-psych.stanford.edu/~span/Publications/gw02ni.pdf)

[xiii] The Metaphorical Structure of the Human Conceptual System (http://www.fflch.usp.br/df/opessoa/Lakoff-Johnson-Metaphorical-Structure.pdf)

[xiv] Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry (http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/amp/34/10/906/)

[xv] Dialogues with the Dalai Lama (http://www.mindandlife.org/dialogues-dalai-lama/)

[xvi] EVOLUTION: AN INTRODUCTION (2nd Edition) by Stephen Stearns & Rolf Hoekstra (2005) Figure 19.1 from p. 481. Figure may be viewed and downloaded for personal scholarly, research and educational use. To reuse the figure in any way permission must first be obtained from Oxford University Press. Figure is not under a Creative Commons license.

Footnote

The article above features as Chapter 8 of the Transpolitica book “Anticipating tomorrow’s politics”. Transpolitica welcomes feedback. Your comments will help to shape the evolution of Transpolitica communications.