By David W. Wood, Executive Director, Transpolitica

Forget left wing versus right wing. The political debate in the medium-term future (10-20 years) will be dominated, instead, by a new set of arguments. These arguments debate the best set of responses to the challenges and opportunities posed by fast-changing technology.

In this essay, I’ll outline four positions: technosceptical, technoconservative, technolibertarian, and technoprogressive. I’ll argue that the first two are non-starters, and I’ll explain why I personally favour the technoprogressive stance over the technolibertarian one.

Accelerating technology

The defining characteristic of the next 10-20 years is the potential ongoing acceleration of technology. Technological development has the potential to progress even more quickly – and to have even larger effects on huge areas of life – than has been the case in the last remarkable 10-20 years.

I share the view expressed by renowned physicist Freeman Dyson, in the book “Infinite in all directions”[i] from his 1985 Gifford lectures:

Technology is… the mother of civilizations, of arts, and of sciences

Technology has given rise to enormous progress in civilization, arts and sciences over recent centuries. New technology is poised to have even bigger impacts on civilization in the next 10-20 years.

MIT professor Andrew McAfee takes up the same theme, in an article published in October last year[ii]: (emphases added)

History teaches us that nothing changes the world like technology

McAfee spells out a “before” and “after” analysis. Here’s the “before”:

For thousands of years, until the middle of the 18th century, there were only glacial rates of population growth, economic expansion, and social development.

And the “after”:

Then an industrial revolution happened, centred around James Watt’s improved steam engine, and humanity’s trajectory bent sharply and permanently upward.

One further quote from McAfee’s article rams home the conclusion:

Great wars and empires, despots and democrats, the insights of science and the revelations of religion – none of them transformed lives and civilizations as much as a few practical inventions.

In principle, many of the grave challenges facing society over the next 10-20 years could be solved by “a few practical inventions”:

- Students complain, with some justification, about the costs of attending university. But technology can enable better MOOCs – Massive Online Open Courses – that can deliver high quality lectures, removing significant parts of the ongoing costs of running universities; free access to such courses can do a lot to help everyone re-skill, as new occupational challenges arise

- With one million people losing their lives to traffic accidents worldwide every year, mainly caused by human driver error[iii], we should welcome the accelerated introduction of self-driving cars

- Medical costs could be reduced by greater application of the principles of preventive maintenance (“a stitch in time saves nine”), particularly through rejuvenation biotechnology[iv] and healthier diets

- A sustained green tech new deal should push society away from dependency on fuels that emit dangerous amounts of greenhouse gases, resulting in lifestyles that are positive for the environment as well as positive for humanity

- The growing costs of governmental bureaucracy itself could be reduced by whole-heartedly embracing improved information technology and lean automation.

Society has already seen remarkable changes in the last 10-20 years as a result of rapid progress in fields such as electronics, computers, digitisation, and automation. In each case, the description “revolution” is appropriate. But even these revolutions pale in significance to the changes that will, potentially, arise in the next 10-20 years from extraordinary developments in healthcare, brain sciences, atomically precise manufacturing, 3D printing, distributed production of renewable energy, artificial intelligence (AI), and improved knowledge management.

Benefits to individuals but threats to society

The potential outputs from accelerating technology can usefully be split into two categories.

The first of these categories is “enhancing humans”. New technologies can provide individual humans with:

- Extra intelligence

- Extra health

- Extra longevity

- Extra material goods

- Extra experiences

- Extra opportunities.

The second category is “disturbing humanity”. This looks, instead, at the drawbacks from new technologies:

- More power placed into the hands of terrorists, criminals, fanatics, and other ne’er-do-wells, to inflict chaos and damage on the rest of us

- More power placed into the hands of governments, and the hands of corporations, to monitor us, and keep track of our every action

- Risks from over-consumption and from the waste products of our lifestyles – including risks to planetary climate stability from excess emissions of greenhouse gases

- Risks of technological unemployment, as growing numbers of people find themselves displaced from the job market by increasingly capable automation (robots, software, and AI)

- So-called “existential risks”, from unintended side-effects of experiments with disease strains, genetic engineering, nanotechnology, or artificial general intelligence.

The content of both categories are extremely weighty. How should politicians react?

The technosceptical response

One response is to deny that technology will have anything like the magnitude of impact that I have just described. This technosceptical response accepts that there has been rapid change over the last 10-20 years, but also observes the following:

- There have been other times of rapid change in the past – as when electrification was introduced, or when railways quickly criss-crossed the world; there is nothing fundamentally different about the present age

- Past inventions such as the washing machine arguably improved lives (especially women’s lives) at least as much as modern inventions such as smartphones

- Although there have been many changes in ICT (information and communications technology) in the last 10-20 years, other areas of technology have slowed down in their progress; for example, commercial jet airliners don’t fly any faster than in the past (indeed they fly a lot slower than Concorde)

- Past expectations of remarkable progress in fields such as flying cars, and manned colonies on Mars, have failed to be fulfilled

- It may well be that the majority of the “low hanging fruit” of technological development has been picked, leaving much slower progress ahead.

Kevin Kelly, the co-founder and former executive editor of Wired, had this to say about progress, in an interview in March 2014[v]:

If we were sent back with a time machine, even 20 years, and reported to people what we have right now and describe what we were going to get in this device in our pocket—we’d have this free encyclopaedia, and we’d have street maps to most of the cities of the world, and we’d have box scores in real time and stock quotes and weather reports, PDFs for every manual in the world—we’d make this very, very, very long list of things that we would say we would have and we get on this device in our pocket, and then we would tell them that most of this content was free. You would simply be declared insane. They would say there is no economic model to make this. What is the economics of this? It doesn’t make any sense, and it seems far-fetched and nearly impossible.

In other words, the last twenty years have, indeed, been remarkable – with progress that would appear “insane” to people from the beginning of that time period. But Kelly then mentions a view that is sceptical about future progress:

There’s a sense that all the big things have happened.

So many big things have happened in the last twenty years. Is there anything left to accomplish? Can science and technology really keep up the same frenetic pace?

Kelly’s answer: We’re by no means at the end of the set of major technological changes. We’re not even at the beginning of these changes:

We’re just at the beginning of the beginning of all these kind of changes.

And for a comparison of what will happen next, to what has happened in the recent past, Kelly predicts that

The next twenty years are going to make this last twenty years just pale.

I share that assessment. I base my views upon the positive feedback cycles which are in place:

- Technology magnifies our knowledge and intelligence, which in turn magnifies our technology

- Technology improves everyone’s ability to access cutting-edge information, via free online encyclopaedias, massive open online courses, and open source software

- Critically, this information is available to vast numbers of bright students, entrepreneurs, hackers, and activists, throughout the emerging world as well as in countries with longer-established modern economies

- Technology improves the ability for smart networking of prospective partners – people in one corner of cyberspace can easily improve and extend ideas that arose elsewhere

- The set of pre-existing component solutions keeps accumulating through its own positive feedback cycles, serving as the basis for yet another round of technological breakthrough.

What’s more, insight, tools, and techniques from one technology area can quickly transfer (often in innovative ways) into new technology areas. This kind of crossover features in what is called “NBIC convergence”:

- The ‘I’ of NBIC is for Information and Communications Technology. It means our ability to store, transmit, and calculate bits of information. It means the transformation of music and videos and newspapers and maps into digital form, which huge impacts for industry.

- The ‘N’ of NBIC is for Nanotechnology. It means our ability to manipulate matter at the atomic level. Nano is one thousand times smaller than Micro, which in turn is one thousand times smaller than Milli. Nanotech enables better and better 3D printing, which is poised to disrupt many industries. It also enables new kinds of material that can be super-light and super-strong, and super-flexible, such as graphene and nanotubes. These new materials will also allow the creation of human-like robots.

- The ‘B’ in NBIC is for Biotechnology. It means our ability to create, not just new kinds of material, but new kinds of life. It means our ability to reprogram, not just the silicon inside transistors, but the long chains of carbon-based DNA inside our cells. We’ll be applying software techniques to re-engineer genes. We’ll be able, if we wish, not just to create so-called “designer babies”, but also “re-designed adults”. With nano-sized computers, sometimes called nanobots, doctors will be able to target very precisely any ailing parts of our body, including cancerous cells, or tangles in the brain, and fix them. And, if we want, we’ll be able to remain perpetually youthful, with nano cosmetic surgery, both outside and inside the body.

- And the ‘C’ in NBIC is for Cognotechnology. It means our ability to understand and improve the basis of cognition – thought and feeling. With very powerful scanners we can understand more precisely what’s going on inside our brains. And we can engineer new moods, new creativity, and (if we wish) new states of ecstasy and bliss.

The real significance of NBIC isn’t just in the four individual areas. It’s in the crossovers between the four fields:

- Nano-sensors allow closer study than ever before of what is happening in the brain

- Insight on how the brain performs its near-miracles of cognition will feed back into new algorithms used in next generation AI

- Improved AI allows systems such as IBM Watson to study vast amounts of medical literature, and then make new suggestions about treating various diseases, etc.

For these reasons, I discount the technosceptical answer. It’s very unlikely that technological progress will run out of steam. However, I am sympathetic in two aspects to the technosceptical position.

First, I don’t see the detailed outcome of technological development as in any way inevitable. The progress that will be made will depend, critically, upon public mood, political intervention, the legislative framework, and so on. It will also depend on the actions of individuals, which can be magnified (via the butterfly effect) to have huge impacts. Specifically, all these factors can alter the timing of various anticipated product breakthroughs.

Second, I do see one way in which the engines of technological progress will become unstuck. That is if society enters a new dark age, via some kind of collapse. This could happen as a result of the influences I listed earlier as “technology disturbing humanity, threatening society”. If technologists ignore these threats, they could well regret what happens next. Plans for improved personal intelligence, health, longevity, etc, could suddenly be undercut by sweeping societal or climatic changes.

That leads me to the second of the four responses that I wish to discuss.

The technoconservative response

Whereas technosceptics say, in effect, “there’s no need to get worked up about the impact of technological change, since that change is going to slow down of its own accord”, technoconservatives say “we need to slow that change down, since otherwise bad things are going to happen – very bad things”.

Technoconservatives take seriously the linkage between ongoing technological change and the threats to society and humanity that I listed earlier. Unless that engine of change is brought under serious control, they say, technology is going to inflict terrible damage on the planet.

For example, many metrics for the health of the environment are near danger points, as a result of human lifestyles that are fuelled by conspicuous consumption. There are major shortages of fresh water. Species are becoming extinct at an unprecedented rate. Some of the accidents that are waiting to happen would make the Fukushima disaster site look like a mild hiccup in comparison. We may be close to a tipping point in global climate, which would trigger the wrong kind of positive feedback cycle (a cycle of increasing warmth). We may also be close to outbreaks of unstoppable pathogens, spread too quickly around the world by criss-crossing jet travellers rushing from one experience to another.

Technoconservatives want to cry out, “Enough!” They want to find ways to apply the brake on our technological steamroller – or (to change the metaphor) to rip out the power cable that keeps the engine of technological progress humming. Where technologists keep putting more opportunities into people’s hands – opportunities to remake what it means to be human – technoconservatives argue for a period of prolonged reflection. “Let’s not play God”, some of them might say. “Let’s be very careful not to let the genie out of the bottle.”

They’ll argue that technology risks leading people astray. Instead of us applying straightforward, ordinary, common-sense solutions to social problems, we’re being beguiled by faux techno-solutions. Instead of authentic, person-to-person relations, we’re spending too much time in front of computer screens, talking to virtual others, neglecting our real-world neighbours. Instead of discovering joy in what’s natural, we’re losing our true nature in quests for technotopia. These quests, argue the technoconservatives, aren’t just misguided. They’re deeply dangerous. We might gain a whole universe of electronic and chemical satiation, but we’ll lose our souls in the process. And not only our souls, but also our lives, if some of the existential risks come to fruition.

But whenever a technoconservative says that technology has already developed enough, and there’s no need for it to continue any further, I’ll point out the vicious impediments that still blight people’s lives the world over – disease, squalor, poverty, ignorance, oppression, aging. It’s true; some of these obstacles could be tackled by non-technological means, such as by politics or social change. But the solutions to other issues lie within the grasp of further scientific and technological progress. Think of the terrible pain still inflicted by numerous diseases, both in young people and in the elderly. Think of the heartache caused by neurodegeneration and dementia. Rejuvenation biotechnology has the latent ability to make all these miseries as much a thing of the past as deaths from tuberculosis, smallpox, typhoid, or the bubonic plague. Anyone who wants to block this progress by proclaiming “Enough” has a great deal of explaining to do.

In any case, is the technoconservative programme feasible? Could the rate of pace of technological change really be significantly slowed down?

Any such action is going to require large-scale globally coordinated agreements. It’s not sufficient for any one company to agree to avoid particular lines of product development. It’s not sufficient for any one country to ban particular fields of technological research. Everyone would need to be brought to the same conclusion, the world over. And everyone would need to be confident that everyone else is going to honour agreements to abstain from various developments.

The problem is, however, that the technology engine is delivering huge numbers of good outputs, in parallel with its bad outputs. And too many people (especially powerful people) are benefiting – or perceive themselves to be benefiting – from these outputs.

Compare the technoconservative thought with the idea that we could switch off the Internet. That would have the outcome of stopping various undesirable activities that currently take place via the Internet – abusive trolling, child pornography, distribution of dangerously substandard counterfeit goods, incitement by fanatical terrorists for impressionable youngsters to join their cause, and so on. But any such mass switch off would also stop all of the other systems which coexist on the Internet with the abovementioned nefarious examples, using the same communications protocols. Systems for commerce, finance, newsflow, entertainment, travel booking, healthcare, social networking, and so on, would all crash to a halt. For good or for ill, we’ve become deeply dependent on these systems. We’re very unlikely to agree to do without them.

Separate from the question of the desirability of shutting down the entire Internet is the question of the feasibility of doing so. After all, the Internet was designed with robustness in mind, including multiple redundancies. Supposedly, it will survive the outbreak of a (minor) nuclear war.

These same two objections – regarding desirability, and regarding feasibility – undermine any thought that the entirety of technological progress could be stopped. The technoconservative approach is too blunt, and is bound to fail.

But while we cannot imagine voluntarily dismantling that great engine of progress, what we can – and should – imagine is to guide that engine more powerfully. Instead of seeking to stop it, we can seek to shape it. That’s the approach favoured by technoprogressives. We’ll come to that shortly.

The technolibertarian response

The technolibertarian view is a near direct opposite of the technoconservative one. Whereas the technoconservatives say “stop – this is going too fast”, technolibertarians say “go faster”.

It’s not that technolibertarians are blind to the threats which cause so much concern to the technoconservatives. On the whole, they’re well aware of these threats. However, they believe that technology, given a free hand, will solve these problems. Technoconservatives, in this analysis, are becoming unnecessarily anxious.

For example, excess greenhouse gases may well be sucked out of the atmosphere by clever carbon capture systems, perhaps involving specially engineered bio-organisms. In any case, green energy sources – potentially including solar, geothermal, biofuels, and nuclear – will soon become cheaper than (and therefore fully preferable to) carbon-based fuels. As for problems with weaponry falling into the wrong hands, suitable defence technology could be created. Declines in biodiversity could be countered by Jurassic Park style technology for species resurrection. Ample fresh water can be generated by desalination processes from sea water, with the energy to achieve this transformation being obtained from the sun. And so on.

This viewpoint has considerable support throughout parts of Silicon Valley, and also finds strong representation in the faculty of Singularity University. Peter Diamandis, co-founder of Singularity University, offers this advice, in a 2014 Forbes article entitled “Turning Big Problems Into Big Business Opportunities”[vi]:

Want to become a billionaire? Then help a billion people.

The world’s biggest problems are the world’s biggest business opportunities.

That’s the premise for companies launching out of Singularity University (SU).

Allow me to explain.

In 2008, Ray Kurzweil and I co-founded SU to enable brilliant graduate students to work on solving humanity’s grand challenges using exponential technologies.

This week we graduated our sixth Graduate Studies Program (GSP) class.

During the GSP, we ask our students to build a company that positively impacts the lives of 1 billion people within 10 years.

Tellingly, Diamandis’ latest book[vii] has the title “Bold”. It’s not called “Go slow”. Nor “Be careful”.

To my mind, there’s a lot to admire in these sentiments. I share the view that technology can provide tools that can allow the solution of the social problems described.

Where things become more contentious, however, is in the attitude of technolibertarians towards the role of government. The main request of technolibertarians to politicians is “hands off”. They want government to provide a free rein to smart scientists, hard-working technologists, and innovative entrepreneurs – a free rein to pursue their ideas for new products. It is these forces, they say, which will produce the solutions to society’s current problems.

Technolibertarians echo the sentiment of Ronald Reagan[viii] that the nine most terrifying words in the English language are, “I’m from the government and I’m here to help.” Governments suffer, in this view, from a number of deep-rooted problems:

- Politicians seek to build empires

- Politicians have little understanding of the latest technologies

- Politicians generally impose outdated regulations – which are concerned with yesterday’s problems rather than with tomorrow’s opportunities

- Regulators are liable to “capture” – an over-influence from vested interests

- Politicians have no ability to pick winners

- Political spending builds a momentum of its own, behind “white elephant” projects.

The technolibertarian recipe to solve social problems, therefore, is technology plus innovation plus free markets, minus intrusive regulations, and minus government interference. The role of government should be minimised – perhaps even privatised.

The technolibertarian spectrum

So far, I’ve given a charitable account of the motivation of technolibertarians. They’re aware of major risks to social well-being, I’ve said. And they want to apply technology to fix these problems.

There’s also a less charitable account, which I’ll mention, since it probably does describe a subset of technolibertarians. That subset has a somewhat different motivation. They don’t particularly care for the well-being of all humanity; rather, they focus on their own well-being. In some cases, they’re prepared to risk the destruction of large swathes of humanity – perhaps even the entirety of humanity. They embrace that risk, because they believe the only way for technological progress to proceed as quickly as possible is to play fast and loose with these risks. For them, the upside of technology achieving its potential is more important than the risk of major collateral damage. They want the possibility of the upside of exponential technology, for themselves, much more than they worry about any downsides of using that technology. In parallel, they’re motivated to find evidence that various existential risks are much less serious than commonly supposed.

Accordingly, there’s a spectrum within the technolibertarian camp of people who hold different motivations to different extents. It may be significant that the full title of the abovementioned recent book by Peter Diamandis[ix] – “Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth and Impact the World” – puts “create wealth” ahead of “impact the world”, as if the latter is a kind of afterthought. The personal success of “going big” has an even higher priority.

A good indication of the range of technolibertarian stances is found in the introductory text of the well-run “Technolibertarians” group on Facebook[x]. It starts as follows:

Technolibertarians is a group of individuals committed to:

- The idea of fostering private governments (often referred to Anarcho-Capitalism), or much smaller forms of the present forms of governments (often referred to as Classical Liberalism and/or Minarchism), both of which support greatly increased amounts of individual freedom in the personal and economic spheres both in and out of the worlds of the Internet;

- Support for increasing the speed of the development of life extending and human-improving technologies, known as Transhumanism (H+), and the same as it regards creation of Strong Artificial Intelligence (also known as Artificial General Intelligence), until the point of reaching the Technological Singularity.

The Technological Singularity is the name given to the envisaged future point when artificial intelligence (AI) is more intelligent, in all relevant dimensions, than humans. The resulting AI is expected to be capable of solving all remaining human problems at that time, for example finding cures to any diseases that remain unsolved. Technolibertarians tend to take it for granted that such an AI will comply with human desires to find such cures, rather than adopting a different worldview in which slow-witted small-minded divisive humankind is seen as an irrelevance or a pest. That’s in line with the general technolibertarian tendency to minimise the potential downsides of fast-changing technology.

The group’s intro continues as follows:

Specifically, we wish to ensure that as technologies in these fields enhance and increase the rate of human evolution without being instruments of oppression, but rather, instruments of freedom for the individual to pursue his or her dreams in whichever manner the best deem fit, and, that these common goals can best be achieved by keeping markets and individuals as unencumbered by governments as possible, for as long as possible, until the Technological Singularity is reached.

The final paragraph of the intro has one point worth noting. That section lists the set of topics which the group asks to be excluded from its discussions:

NOTE: Proponents of things like anti-GMO/anti-vaccine luddism, chemtrailers, 9/11 truthers, Zeitgeist/Venus Project, and Raelianism, Climate alarmism, and other pseudoscientific beliefs are unwelcome to promote their unscientific irrational moonbattery in this group. Avoid logical fallacies, stick to facts.

The inclusion of “Climate alarmism” in this list of “pseudoscientific beliefs” and “unscientific moonbattery” is a reminder of the technolibertarian opposition to any focus on the potential drawbacks of misuse of technology. In that view, there’s no need to stir up any alarm about the potential for rapid climate change. Instead, provided politicians and regulators are kept out of the way, technologists and entrepreneurs will ensure that the climate remains hospitable.

The technoprogressive response

Technoprogressives share with technolibertarians the core proposition sometimes called “the central meme of transhumanism”[xi] – that it is that it is ethical and desirable to improve the human condition through technology. Both positions see very important positive roles for science and technology, and also for the productive energies that can be unleashed by entrepreneurs, start-ups, and other business groupings. The difference between the positions is in the question of whether political and legislative intervention can have positive outcomes. Both groups are aware that, in practice, political and legislative intervention is often cumbersome, self-serving, misguided, and unnecessarily hinders the speedy development of innovative products. The groups differ in whether it’s worth seeking better politics and better legislation.

The central meme of social futurism[xii] (which is a kind of synonym for the technoprogressive standpoint) states, analogously to the central meme of transhumanism, that it is ethical and desirable to improve society through technology. Technology isn’t just restricted to improving the human body and mind – doing better than Darwinian natural selection. It’s capable of improving human politics and human economics – doing better than the invisible hand of free markets. (Though, in both cases, modifications need to be approached with care.)

Some phrases from the Technoprogressive Declaration[xiii] – created in November 2014 – highlight the distinctive position taken by technoprogressives:

The world is unacceptably unequal and dangerous. Emerging technologies could make things dramatically better or worse. Unfortunately too few people yet understand the dimensions of both the threats and rewards that humanity faces. It is time for technoprogressives, transhumanists and futurists to step up our political engagement and attempt to influence the course of events.

Our core commitment is that both technological progress and democracy are required for the ongoing emancipation of humanity from its constraints…

We must intervene to insist that technologies are well-regulated and made universally accessible in strong and just societies. Technology could exacerbate inequality and catastrophic risks in the coming decades, or especially if democratized and well-regulated, ensure longer, healthy and more enabled lives for growing numbers of people, and a stronger and more secure civilization…

As artificial intelligence, robotics and other technologies increasingly destroy more jobs than they create, and senior citizens live longer, we must join in calling for a radical reform of the economic system. All persons should be liberated from the necessity of the toil of work. Every human being should be guaranteed an income, healthcare, and life-long access to education.

Evidently, this Declaration aims at liberation – similar to the technolibertarian stance. But the methods in the Declaration listed include

- Radical reform of the economic system

- Smart regulation of new technologies

- The democratisation of access to new technologies

- Stepping up political engagement.

Another distinctive aspect of the Technoprogressive Declaration is in its recurring references to inequality. Indeed, the very first phrase is “The world is unacceptably unequal”. The picture accompanying the Declaration on the IEET website carries the word “egalitarianism” – the principle that all people deserve equal rights and opportunities.

To sharpen our understanding of the differences between technolibertarians and technoprogressives, let’s look more closely at this question of inequality – a topic which is strikingly missing from the introductory definition on the Facebook “Technolibertarians” group.

Growing inequality

Publications[xiv] over the last few years by researchers such as Thomas Piketty[xv] and Emmanuel Saez[xvi] make it undeniable that, in many countries, including the US and the UK, the share of income being received by upper fractions of the population is rising to levels unprecedented since before the great depression of the 1930s. For example, the best paid 10% in the US now receive just over 50% of the total income in that country – up from around 35% over the 1940s, 50s, 60s, and 70s.

The Economist magazine noted in a November 2014 article[xvii], in a section headlined “The really, really rich get much, much richer”:

The fortunes of the wealthy have grown, especially at the very top. The 16,000 families making up the richest 0.01%, with an average net worth of $371m, now control 11.2% of total wealth—back to the 1916 share, which is the highest on record.

Similar trends apply throughout Western Europe (though less extreme).

Similar trends exist in Russia. Writing in October 2013, Ron Synovitz reported findings[xviii] from the annual global wealth study published by the financial services group Credit Suisse:

A new report on global wealth has determined that Russia now has the highest level of wealth inequality in the world – with the exception of a few small Caribbean nations where billionaires have taken up residency… A mere 110 Russian citizens now control 35 percent of the total household wealth across the vast country.

By comparison, billionaires worldwide account for just 1 to 2 percent of total wealth.

The report says Russia has one billionaire for every $11 billion in wealth while, across the rest of the world, there is one billionaire for every $170 billion.

Billionaire investor Warren Buffet – the admired “sage of Omaha” who has contributed large amounts of his own personal wealth to philanthropic ventures – commented drily as follows[xix]:

There’s been class warfare going on for the last 20 years, and my class has won. We’re the ones that have gotten our tax rates reduced dramatically.

If you look at the 400 highest taxpayers in the United States in 1992, the first year for figures, they averaged about $40 million of [income] per person. In [2010], they were $227 million per person… During that period, their taxes went down from 29 percent to 21 percent of income.

The raw statistics are incontrovertible. Where there’s scope for debate is in the interpretation of the figures.

Many people respond that inequality of outcome is no big deal. People are different, and that it’s right that their different efforts and talents are rewarded differently. I’ll come back in a moment to the question of the degree of the inequality of outcome, and whether that extreme is good for society. But we also need to look at the growing inequality of opportunity. The relevant dynamics were summed up evocatively in a recent perceptive speech in Washington[xx]. The speech explored the background to frustrations being expressed by US voters about the performance of their politicians. Here are some brief excerpts:

People’s… frustration is rooted in their own daily battles – to make ends meet, to pay for college, buy a home, save for retirement. It’s rooted in the nagging sense that no matter how hard they work, the deck is stacked against them. And it’s rooted in the fear that their kids won’t be better off than they were. They may not follow the constant back-and-forth in Washington or all the policy details, but they experience in a very personal way the relentless, decades-long trend that I want to spend some time talking about today. And that is a dangerous and growing inequality and lack of upward mobility that has jeopardized middle-class America’s basic bargain – that if you work hard, you have a chance to get ahead.

I believe this is the defining challenge of our time…

While we don’t promise equal outcomes, we have strived to deliver equal opportunity – the idea that success doesn’t depend on being born into wealth or privilege, it depends on effort and merit…

We’ve never begrudged success in America. We aspire to it. We admire folks who start new businesses, create jobs, and invent the products that enrich our lives. And we expect them to be rewarded handsomely for it. In fact, we’ve often accepted more income inequality than many other nations for one big reason – because we were convinced that America is a place where even if you’re born with nothing, with a little hard work you can improve your own situation over time and build something better to leave your kids…

The problem is that alongside increased inequality, we’ve seen diminished levels of upward mobility in recent years. A child born in the top 20% has about a 2-in-3 chance of staying at or near the top. A child born into the bottom 20% has a less than 1-in-20 shot at making it to the top. He’s 10 times likelier to stay where he is.

The speech was made by US President Barack Obama, and is worth reading in full[xxi], regardless of your own political leanings (Republican, Democrat, or whatever).

Responses to growing inequality

Let’s look again at the changes in tax rate experienced by the top 400 taxpayers in the US, over the period 1992 to 2010. While the average income in that group soared more than five-fold – from $40M to $227M – the tax-rate fell from 29% to 21%.

In my experience, technolibertarians have three responses to statistics of this sort. First, they sometimes assert that the people benefiting from these hugely increased incomes (and declining tax rates) uniquely deserve these benefits. The market has delivered these benefits to them, and the market is always right. Second, they may point out that the tax office is a lot better off with 21% of $227M than with 29% of $40M. Third, they say that even if the rich are seeing their wealth rise faster than before, the poor are also becoming wealthier – so we are switching from a world of “haves and have-nots” to a world of “have-a-lots and haves”. In this new world, even the poorest (if they manage their lives sensibly) can access a swathe of goods that would have been viewed in previous times as spectacular luxuries.

There’s a gist of truth in all three answers. Changing market circumstances mean that winning companies do take a larger share of rewards that in previous times. The factors behind “winner takes all” outcomes are described in, for example, the book “The Second Machine Age”[xxii] by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, of MIT:

- The digitization of more and more information, goods, and services

- The vast improvements in telecommunications and transport – the best products can be used in every market

- The increased importance of networks and standards – new capabilities and new ideas can be combined and recombined more quickly.

This effect is also known as “the economics of superstars”, using a term coined in 1981[xxiii] by Sherwin Rosen:

The phenomenon of Superstars, wherein relatively small numbers of people earn enormous amounts of money and dominate the activities in which they engage, seems to be increasingly important in the modern world.

This analysis explains why the photo sharing company Instagram, with only 13 employees at the time (but with 100 million registered users) was valued at $1B when acquired by Facebook in April 2012. In contrast, another company in the field of photography, Kodak, had its peak valuation of $30B in 1997, when it had 86,000 employees. This implies that Instagram employees had, on average, 2,000 times the productivity of Kodak employees. This productivity advantage was due to how Instagram took special advantage of pre-existing technology.

The analysis is continued in a landmark MIT Technology Review article by David Rotman, “Technology and inequality”[xxiv]:

The signs of the gap—really, a chasm—between the poor and the super-rich are hard to miss in Silicon Valley. On a bustling morning in downtown Palo Alto, the center of today’s technology boom, apparently homeless people and their meager belongings occupy almost every available public bench. Twenty minutes away in San Jose, the largest city in the Valley, a camp of homeless people known as the Jungle—reputed to be the largest in the country—has taken root along a creek within walking distance of Adobe’s headquarters and the gleaming, ultramodern city hall.

The homeless are the most visible signs of poverty in the region. But the numbers back up first impressions. Median income in Silicon Valley reached $94,000 in 2013, far above the national median of around $53,000. Yet an estimated 31 percent of jobs pay $16 per hour or less, below what is needed to support a family in an area with notoriously expensive housing. The poverty rate in Santa Clara County, the heart of Silicon Valley, is around 19 percent, according to calculations that factor in the high cost of living.

Even some of the area’s biggest technology boosters are appalled. “You have people begging in the street on University Avenue [Palo Alto’s main street],” says Vivek Wadhwa, a fellow at Stanford University’s Rock Center for Corporate Governance and at Singularity University, an education corporation in Moffett Field with ties to the elites in Silicon Valley. “It’s like what you see in India,” adds Wadhwa, who was born in Delhi. “Silicon Valley is a look at the future we’re creating, and it’s really disturbing.”

Rotman goes on to quote legendary venture capitalist Steve Jurvetson, Managing Director at Draper Fisher Jurvetson. Jurvetson was an early investor in Hotmail and sits on the boards of SpaceX, Synthetic Genomics, and Tesla Motors:

“It just seems so obvious to me [that] technology is accelerating the rich-poor gap,” says Steve Jurvetson… In many discussions with his peers in the high-tech community, he says, it has been “the elephant in the room, stomping around, banging off the walls.”

Just because there is strong market logic to the way in which technological superstars are able to command ever larger incomes, this does not mean, of course, that we should acquiesce in this fact. An “is” does not imply an “ought”. Even an enlightened self-interest should cause a rethink within “the 1%” (and their supporters on lower incomes – who often aspire to being to reach these stellar salary levels themselves). A plea for such a rethink[xxv] was issued by one of its members, Nick Hanauer. Hanauer introduced himself as follows:

You probably don’t know me, but like you I am one of those .01%ers, a proud and unapologetic capitalist. I have founded, co-founded and funded more than 30 companies across a range of industries—from itsy-bitsy ones like the night club I started in my 20s to giant ones like Amazon.com, for which I was the first nonfamily investor. Then I founded aQuantive, an Internet advertising company that was sold to Microsoft in 2007 for $6.4 billion. In cash. My friends and I own a bank. I tell you all this to demonstrate that in many ways I’m no different from you. Like you, I have a broad perspective on business and capitalism. And also like you, I have been rewarded obscenely for my success, with a life that the other 99.99 percent of Americans can’t even imagine. Multiple homes, my own plane, etc., etc.

But Hanauer was not writing to boast. He was writing to warn. The title of his article made that clear: “The Pitchforks Are Coming… For Us Plutocrats”. This extract conveys the flavour:

The problem isn’t that we have inequality. Some inequality is intrinsic to any high-functioning capitalist economy. The problem is that inequality is at historically high levels and getting worse every day. Our country is rapidly becoming less a capitalist society and more a feudal society. Unless our policies change dramatically, the middle class will disappear, and we will be back to late 18th-century France. Before the revolution.

And so I have a message for my fellow filthy rich, for all of us who live in our gated bubble worlds: Wake up, people. It won’t last.

If we don’t do something to fix the glaring inequities in this economy, the pitchforks are going to come for us. No society can sustain this kind of rising inequality. In fact, there is no example in human history where wealth accumulated like this and the pitchforks didn’t eventually come out. You show me a highly unequal society, and I will show you a police state. Or an uprising.

Declining costs

But what about the declining costs of both the necessities and the luxuries of life? Won’t the imminent material abundance, enabled by exponential technologies, remove the heartaches caused by present-day inequalities? Here, the technolibertarians have a fair point.

After all, Mary Meeker’s annual KPCB reviews of Internet trends contain some eye-popping statistics of declining costs. Here are some call-outs from her 2014 presentation[xxvi]:

- Computational costs have declined 33% annually from 1990 to 2013: a million transistors cost $527 in 1990 but only 5 cents in 2013

- Storage costs declined 38% annually from 1992 to 2013: a Gigabyte of storage came down in price over that time from $569 to 2 cents

- Bandwidth costs declined 27% annually from 1999 to 2013: connectivity of 1 Gbps came down in price over that time from $1,245 to $16

- Even smartphones, despite their ever-greater functionality, have seen their costs decline 5% annually from 2008 to 2013.

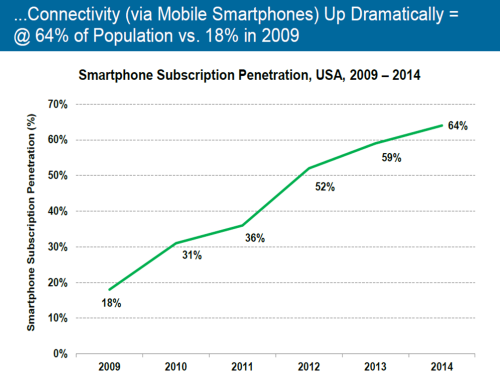

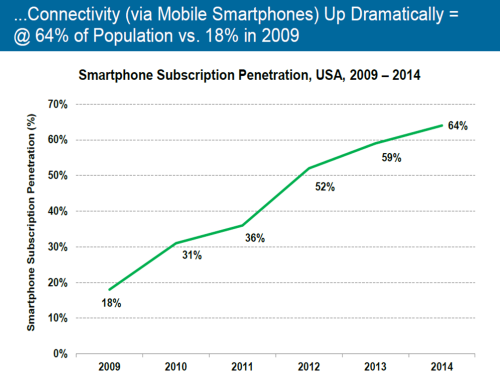

One result of that final trend – as reported in Meeker’s KPCB presentation in 2015[xxvii] – is that smartphone US market penetration jumped up from 18% in 2009 to 64% in 2014. Even in the US, with all its manifest inequalities, access to smartphones evidently extends far beyond the 1%. That access brings, in turn, the opportunity to browse much more information, 24×7, than was available even to US Presidents just a couple of decades ago.

Yuri Van Geest of the Singularity University picks up the analysis, in an attractive slideset introduction[xxviii] to his book “Exponential Organizations”.[xxix]. These slides illustrate remarkable price reductions for (broadly) like-for-like functionality in a range of fast-improving technological fields:

- Industrial robots: 23-fold reduction in 5 years

- Neurotech devices for brain-computer interface (BCI): 44-fold reduction in 5 years

- Autonomous flying drones: 142-fold reduction in 6 years

- 3D-printing: 400-fold reduction in 7 years

- Full DNA sequencing: 10,000-fold reduction (from $10M to $1,000) in 7 years.

Similar price reductions, it can be argued, will take all the heat out of present-day unequal access to goods. In the meantime, technolibertarians urge two sets of action:

- Let’s press forwards quickly with further technological advances

- Let’s avoid obsessing about present-day inequalities (and, especially, the appearance of present-day inequalities), since the more they’re spoken about, the greater the likelihood of people becoming upset about them and taking drastic action.

However, at the same time as technology can reduce prices of products that have already been invented, it can result in the creation of fabulous new products. Some of these new products start off as highly expensive – especially in fields such as advanced healthcare. Sectors such as rejuvenation biotech and neuro-enhancement may well see the following outcomes:

- Initial therapies are expensive, but deliver a decisive advantage to the people who can afford to pay for them

- With their brains enhanced – and with their bodies made more youthful and vigorous – the “winner takes all” trend will be magnified

- People who are unable to pay for these treatments will therefore fall even further behind

- Social alienation and angst will grow, with potentially explosive outcomes.

A counter-argument is that enterprising companies will be motivated to quickly make products available at lower cost. Rather than pursuing revenues from small populations of wealthy consumers, they will set their eyes on the larger populations of consumers with lower incomes. But if the raw cost of the product itself remains high, that may not be easy. Apple’s policy of targeting the wealthier proportion of would-be smartphone users makes good sense in its own terms.

A similar policy – this time by pharmaceutical giant Bayer – was described in an article by Glyn Moody in early 2014[xxx]. The article carried the headline “Bayer’s CEO: We Develop Drugs For Rich Westerners, Not Poor Indians”. It quoted Bayer Chief Executive Officer Marijn Dekkers as follows:

We did not develop this medicine for Indians. We developed it for western patients who can afford it.

That policy aligns with the for-profit motivation that the company pursues, in service of the needs of its shareholders to maximise returns. But as Moody points out, pharmaceutical companies have, in the past, shown broader motivation. He refers to this quote from 1950 from George Merck[xxxi] (emphasis added):

We try never to forget that medicine is for the people. It is not for the profits. The profits follow, and if we have remembered that, they have never failed to appear. The better we have remembered it, the larger they have been…

We cannot step aside and say that we have achieved our goal by inventing a new drug or a new way by which to treat presently incurable diseases, a new way to help those who suffer from malnutrition, or the creation of ideal balanced diets on a worldwide scale. We cannot rest till the way has been found, with our help, to bring our finest achievement to everyone.

What determines whether the narrow financial incentives of the market govern behaviours of companies with the technology (possibly unique technology) that enables significant human enhancement? Other factors need to come into play – not just financial motivation.

The genius – and limits – of free markets

Even within their own parameters – the promotion of optimal trade and the accumulation of wealth – free markets often fail. The argument for smart oversight and regulation of markets is well made in the 2009 book “How markets fail: the logic of economic calamities”[xxxii] by the New Yorker journalist John Cassidy[xxxiii].

The book contains a sweeping but compelling survey of a notion Cassidy dubs “Utopian economics”, before providing layer after layer of decisive critique of that notion. As such, the book provides a very useful guide to the history of economic thinking, covering Adam Smith, Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, John Maynard Keynes, Arthur Pigou, Hyman Minsky, among others.

The key theme in the book is that markets do fail from time to time, potentially in disastrous ways, and that some element of government oversight and intervention is both critical and necessary, to avoid calamity. This theme is hardly new, but many people resist it, and the book has the merit of marshalling the arguments more comprehensively than I have seen elsewhere.

As Cassidy describes it, “utopian economics” is the widespread view that the self-interest of individuals and agencies, allowed to express itself via a free market economy, will inevitably produce results that are good for the whole economy. The book starts with eight chapters that sympathetically outline the history of thinking about utopian economics. Along the way, he regularly points out instances when free market champions nevertheless described cases when government intervention and control was required. For example, referring to Adam Smith, Cassidy writes:

Smith and his successors … believed that the government had a duty to protect the public from financial swindles and speculative panics, which were both common in 18th and 19th century Britain…

To prevent a recurrence of credit busts, Smith advocated preventing banks from issuing notes to speculative lenders. “Such regulations may, no doubt, be considered as in some respects a violation of natural liberty”, he wrote. “But these exertions of the natural liberty of a few individuals, which might endanger the security of the whole society, are, and ought to be, restrained by the laws of all governments… The obligation of building party walls [between adjacent houses], in order to prevent the communication of a fire, is a violation of natural liberty, exactly of the same kind with the regulations of the banking trade which are here proposed.”

The book identifies long-time Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan as one of the villains of the great financial crash of 2007-2009. Cassidy quotes a reply given by Greenspan[xxxiv] to the question “Were you wrong” asked of him in October 2008 by the US House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform:

“I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interest of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in the firms…”

Greenspan was far from alone in his belief in the self-correcting power of economies in which self-interest is allowed to flourish. There were many reasons for people to hold that belief. It appeared to be justified both theoretically and empirically. As Greenspan remarked,

“I have been going for forty years, or more, with very considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well.”

Cassidy devotes another eight chapters to reviewing the history of criticisms of utopian economics. This part of the book is entitled “Reality-based economics”, and covers topics such as:

- Game theory (“the prisoners dilemma”),

- Behavioural economics (pioneered by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky) – including disaster myopia,

- Problems of spillovers and externalities (such as pollution) – which can only be fully addressed by centralised collective action,

- Drawbacks of hidden information and the failure of “price signalling”,

- Loss of competiveness when monopoly conditions are approached,

- Flaws in banking risk management policies (which drastically under-estimated the consequences of larger deviations from “business as usual”),

- Problems with asymmetric bonus structure,

- The perverse psychology of investment bubbles.

In summary, Cassidy lists four “illusions” of utopian economics:

- The illusion of harmony: that free markets always generate good outcomes;

- The illusion of stability: that free market economy is sturdy;

- The illusion of predictability: that distribution of returns can be foreseen;

- The illusion of Homo Economicus: that individuals are rational and act on perfect information.

These illusions remain pervasive in many parts of economic thought. These illusions also lie behind technolibertarian optimism that technology, without government intervention, will be able to solve social and climatic problems such as terrorism, surveillance, environmental devastation, and threats from new pathogens.

Indeed, free markets and innovative technology have, together, been a tremendous force for progress in recent history. However, they need smart oversight and regulation if they are going to reach their fullest potential. That thought lies at the core of the technoprogressive stance.

The political landscape ahead

The need for smart oversight and regulation will grow even more pressing, as technology progresses over the next few decades to the point of displacing ever larger numbers of people from the workforce. This scenario is described in the recent book by Martin Ford, “Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future”[xxxv].

In the scenarios Ford describes, technological unemployment won’t just impact the lesser skilled jobs currently undertaken by people in, say, the lower 50% of the income spectrum. It will also bite into the skills used by many of the top 5% in their work. As a result, many people who presently instinctively rebel against any technoprogressive notion of a new social contract may find their worldview turned upside down.

Other growing social crises may well accelerate similar changes in mindset. For example, as threats to personal well-being from poor software security become more widely publicised – as covered in my recent article “Eating the world: the growing importance of software security”[xxxvi] – I expect a growing public clamour for government action to tilt the software security playing field. Any idea of a laissez-faire market in software vulnerabilities will become seen as an irresponsible indulgence. Likewise for any idea about a laissez-faire market in synthetic pathogens, potential nano-weaponry, and lots more besides.

In short: To the extent that they place whole-hearted trust in free markets, technolibertarians are indulging in a dangerous fantasy.

But I say all this out of no desire to see the technolibertarian viewpoint be crushed. After all, that viewpoint puts its finger on a set of valid concerns, which need to be integrated into our collective response to technological possibilities. Governments and regulatory schemes suffer, as mentioned earlier, from tendencies towards deep problems: empire-building, poor understanding of new tech, regulations that become outdated, regulatory capture, and white elephant projects.

So rather than technoprogressives somehow vanquishing technolibertarians, in debate over the next 5-10 years, I look forwards to the best insights of both positions being integrated. The governmental and regulatory systems of the near future need to be significantly enhanced versions of today’s incumbent systems. We need government 2.0 and regulations 2.0.

Thinkers whose instincts place them firmly within the technolibertarian heritage can actively contribute to this discussion. As an example of this kind of positive contribution, Swedish think-tank Eudoxa founder Waldemar Ingdahl writes as follows in his essay “Anarchy beyond socialism and capitalism”[xxxvii] in the first Transpolitica book, “Anticipating tomorrow’s politics”[xxxviii]:

This essay draws attention to a variant of anarchism – market anarchism – which has been little studied, but whose relevance may increase due to new technology…

Market anarchism is a belief centred on mutual exchange, not economic privilege, advocating freed markets, not capitalism. Social justice is mainly seen as eliminating the governmental privileges that rigs the market in favour of capitalists while retaining a focus on building voluntary institutions such as cooperatives.

Market anarchism pronounces itself a radical liberation while empowering people to eliminate structural poverty, and redistribute economic and social power. It differs from left-wing anarchism by its embrace of markets, while setting itself apart from the anarcho-capitalist view of freedom as simply being present day corporations and capitalist structures, minus the state’s taxes and regulations.

Indeed, there is much more that unifies technolibertarians and technoprogressives than what divides them. They can both be seen as part of what pioneering futurist FM Esfandiary[xxxix] called “up wing” as opposed to either “right wing” or “left wing”. In this, these two positions are opposed to the “down wing” technoconservative position, as well as to the “no wing” technosceptical position. Esfandiary also endorsed the term “transhuman”, via his 1989 book “Are You a Transhuman?: Monitoring and Stimulating Your Personal Rate of Growth in a Rapidly Changing World”.

Accordingly, I look forward to the following features of the political dialogue of the next 10-20 years:

- The evolution and maturation of an integrated transhumanist political position, that respects and enhances the best insights of both technolibertarians and technoprogressives

- The growing recognition of the fundamental inadequacies of both the technoconservative and technosceptical viewpoints.

Given the inertia present in current political systems and prevailing mindsets, the second of these tasks may prove harder than the first. But the first may turn out to be the enabler for the second. It is that task that deserves our fullest attention.

References

[i] http://www.amazon.co.uk/Infinite-All-Directions-Freeman-Dyson/dp/0060915692/

[ii] http://blogs.ft.com/andrew-mcafee/2014/10/16/were-living-through-a-new-industrial-revolution/

[iii] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/motoring/road-safety/8702111/How-do-accidents-happen.html

[iv] http://www.sens.org/outreach/rejuvenation-biotechnology-conference-2015

[v] http://edge.org/conversation/the-technium

[vi] http://www.forbes.com/sites/peterdiamandis/2014/08/25/how-to-become-a-billionaire/

[vii] http://www.diamandis.com/bold/

[viii] http://www.reaganfoundation.org/reagan-quotes-detail.aspx?tx=2079

[ix] http://www.diamandis.com/bold/

[x] https://www.facebook.com/groups/technolibertarians/

[xi] https://wavism.wordpress.com/2012/05/10/cmzs-central-meme-of-zero-state/

[xii] https://wavism.wordpress.com/2012/05/10/cmzs-central-meme-of-zero-state/

[xiii] http://ieet.org/index.php/IEET/more/tpdec2014

[xiv] http://www.newyorker.com/news/john-cassidy/pikettys-inequality-story-in-six-charts

[xv] http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capital21c/en/pdf/F0.I.1.pdf

[xvi] http://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2012.pdf

[xvii] http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21631129-it-001-who-are-really-getting-ahead-america-forget-1

[xviii] http://www.rferl.org/content/russia-billionaire-wealth-inequality/25132471.html

[xix] http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/plum-line/post/theres-been-class-warfare-for-the-last-20-years-and-my-class-has-won/2011/03/03/gIQApaFbAL_blog.html

[xx] http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/12/04/the-best-speech-obama-has-given-on-the-economy/

[xxi] http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/12/04/the-best-speech-obama-has-given-on-the-economy/

[xxii] http://www.secondmachineage.com/

[xxiii] http://users.polisci.wisc.edu/schatzberg/ps616/Rosen1981.pdf

[xxiv] http://www.technologyreview.com/featuredstory/531726/technology-and-inequality/

[xxv] http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/06/the-pitchforks-are-coming-for-us-plutocrats-108014.html

[xxvi] http://www.businessinsider.com.au/mary-meekers-2014-internet-presentation-2014-5

[xxvii] http://www.slideshare.net/kleinerperkins/internet-trends-v1

[xxviii] http://www.slideshare.net/vangeest/exponential-organizations-h

[xxix] http://www.exponentialorgs.com/

[xxx] https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20140124/09481025978/big-pharma-ceo-we-develop-drugs-rich-westerners-not-poor.shtml

[xxxi] http://todayinsci.com/M/Merck_George/MerckGeorge-Quotations.htm

[xxxii] http://www.amazon.com/How-Markets-Fail-Economic-Calamities/dp/0374173206/

[xxxiii] http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/bios/john_cassidy/search?contributorName=john%20cassidy

[xxxiv] http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/23/business/worldbusiness/23iht-gspan.4.17206624.html

[xxxv] http://www.amazon.com/Rise-Robots-Technology-Threat-Jobless/dp/0465059996

[xxxvi] http://dw2blog.com/2015/06/11/eating-the-world-the-growing-importance-of-software-security/

[xxxvii] https://transpolitica.org/2015/06/13/anarchy-beyond-socialism-and-capitalism/

[xxxviii] https://transpolitica.org/publications/anticipating-tomorrows-politics/

[xxxix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FM-2030

Footnote

The article above features as Chapter 2 of the Transpolitica book “Envisioning Politics 2.0”.